Bartleby Student Success Unsubscribe

| 'Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street' | |

|---|---|

| Author | Herman Melville |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Short story |

| Published in | Putnam's Magazine |

| Publication type | Periodical |

| Publication date | November–December 1853 |

'Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street' is a short story by the American writer Herman Melville, first serialized anonymously in two parts in the November and December 1853 issues of Putnam's Magazine, and reprinted with minor textual alterations in his The Piazza Tales in 1856. In the story, a Wall Street lawyer hires a new clerk who, after an initial bout of hard work, refuses to make copy or do any other task required of him, with the words 'I would prefer not to'.

Numerous critical essays have been published on the story, which scholar Robert Milder describes as 'unquestionably the masterpiece of the short fiction' in the Melville canon.[1]

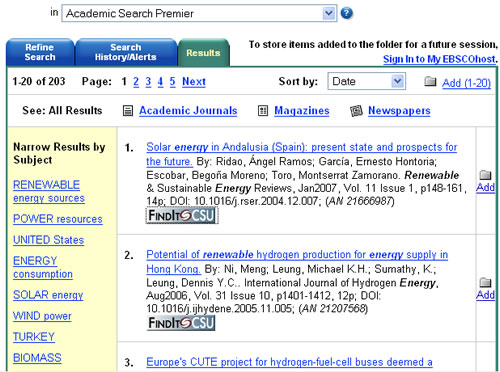

Bartleby.com provides free Web access to a comprehensive collection of reference, verse, fiction, and nonfiction works. AESTHETICS: The pages are attractive, and the layout is consistent throughout the site. ORGANIZATION: Navigate the site by choosing one of the content areas from a pull-down menu. Additionally, The Lawyer showcases the inability of language to connect people, as every one of his attempts to get to know Bartleby fail. Further, even The Lawyer’s writing of this story itself—which delves into The Lawyer’s complex feelings for Bartleby—is an example of language failing to connect, as Bartleby himself is deceased,.

- 4Analysis

- 8Adaptations and references

- 8.2References to

Plot[edit]

The narrator is an elderly, unnamed Manhattan lawyer with a comfortable business in legal documents. He already employs two scriveners, Nippers and Turkey, to copy legal documents by hand, but an increase in business leads him to advertise for a third. He hires the forlorn-looking Bartleby in the hope that his calmness will soothe the irascible temperaments of the other two. An office boy nicknamed Ginger Nut completes the staff.

Dewa 19 ari lasso mp3. At first, Bartleby produces a large volume of high-quality work, but one day, when asked to help proofread a document, Bartleby answers with what soon becomes his perpetual response to every request: 'I would prefer not to.' To the dismay of the narrator and the irritation of the other employees, Bartleby performs fewer and fewer tasks and eventually none, instead spending long periods of time staring out one of the office's windows at a brick wall. The narrator makes several futile attempts to reason with Bartleby and to learn something about him; when the narrator stops by the office one Sunday morning, he discovers that Bartleby has started living there.

Tension builds as business associates wonder why Bartleby is always there. Sensing the threat to his reputation but emotionally unable to evict Bartleby, the narrator moves his business out. Soon the new tenants come to ask for help in removing Bartleby, who now sits on the stairs all day and sleeps in the building's doorway at night. The narrator visits Bartleby and attempts to reason with him; to his own surprise, he invites Bartleby to live with him, but Bartleby declines the offer. Later the narrator returns to find that Bartleby has been forcibly removed and imprisoned in the Tombs. Finding Bartleby glummer than usual during a visit, the narrator bribes a turnkey to make sure he gets enough food. When the narrator returns a few days later to check on Bartleby, he discovers that he died of starvation, having preferred not to eat.

Sometime afterwards, the narrator hears a rumor that Bartleby had worked in a dead-letter office and reflects that dead letters would have made anyone of Bartleby's temperament sink into an even darker gloom. The story closes with the narrator's resigned and pained sigh, 'Ah Bartleby! Ah humanity!'

Composition[edit]

Melville's major source for the story was an advertisement for a new book, The Lawyer's Story, printed in both the Tribune and the Times on February 18, 1853. The book was published anonymously later that year but in fact was written by popular novelist James A. Maitland.[2] This advertisement included the complete first chapter, which had the following opening sentence: 'In the summer of 1843, having an extraordinary quantity of deeds to copy, I engaged, temporarily, an extra copying clerk, who interested me considerably, in consequence of his modest, quiet, gentlemanly demeanor, and his intense application to his duties'. Melville biographer Hershel Parker points out that nothing else in the chapter besides this 'remarkably evocative sentence' was 'notable'.[3] Critic Andrew Knighton notes the debt of the story to an obscure work from 1846, Robert Grant White's Law and Laziness: or, Students at Law of Leisure. This source contains one scene and many characters—including an idle scrivener—that appear to have influenced Melville's narrative.[4]

Melville may have written the story as an emotional response to the bad reviews garnered by Pierre, his preceding novel.[5] Christopher Sten suggests that Melville found inspiration in Ralph Waldo Emerson's essays, particularly 'The Transcendentalist' which shows parallels to 'Bartleby'.[6]

Autobiographical interpretations[edit]

Bartleby is a scrivener—a kind of clerk or a copyist—'who obstinately refuses to go on doing the sort of writing demanded of him'. During the spring of 1851, Melville felt similarly about his work on Moby Dick. Thus, Bartleby may represent Melville's frustration with his own situation as a writer, and the story itself is 'about a writer who forsakes conventional modes because of an irresistible preoccupation with the most baffling philosophical questions'.[7] Bartleby may also be seen to represent Melville's relation to his commercial, democratic society.[8]

Melville made an allusion to the John C. Colt case in this short story. The narrator restrains his anger toward Bartleby, his unrelentingly difficult employee, by reflecting upon 'the tragedy of the unfortunate Adams and the still more unfortunate Colt and how poor Colt, being dreadfully incensed by Adams .. was unawares hurled into his fatal act'.[9][10]

Analysis[edit]

Bartleby's character can be read in a variety of ways. Based on the perception of the narrator and the limited details supplied in the story, his character remains elusive even as the story comes to a close.

As an example of clinical depression[edit]

Bartleby shows classic symptoms of depression, especially his lack of motivation. He is a passive person, although he is the only reliable worker in the office other than the narrator and Ginger Nut. Bartleby is a good worker until he starts to refuse to do his work. Bartleby does not divulge any personal information to the narrator. Bartleby's death suggests the effects of depression—having no motivation to survive, he refrains from eating until he dies.[11]

As a reflection of the narrator[edit]

Bartleby's character can be interpreted as a 'psychological double' for the narrator that criticizes the 'sterility, impersonality, and mechanical adjustments of the world which the lawyer inhabits'.[12] Until the very end of the short story, the work gives the reader no history of Bartleby. This lack of history suggests that Bartleby may have just sprung from the narrator's mind. Also consider the narrator's behavior around Bartleby: screening him off in a corner where he can have his privacy 'symbolizes the lawyer's compartmentalization of the unconscious forces which Bartleby represents'.[12]

The psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas insists the story is more about the narrator than the narrated. 'The narrator's willingness to tolerate [Bartleby's] work stoppage is what needs to be explained .. . As the story proceeds, it becomes increasingly clear that the lawyer identifies with his clerk. To be sure, it is an ambivalent identification, but that only makes it all the more powerful'.[13]

Analysis of the narrator[edit]

The narrator, Bartleby's employer, provides a first-person narration of his experiences working with Bartleby. He portrays himself as a generous man, although there are instances in the text that question his reliability. His kindness may be derived from his curiosity and fascination for Bartleby. Moreover, once Bartleby's work ethic begins to decline, the narrator still allows his employment to continue, perhaps out of a desire to avoid confrontation. He also portrays himself as tolerant towards the other employees, Turkey and Nippers, who are unproductive at different points in the day; however, this simply re-introduces the narrator's non-confrontational nature. Throughout the story, the narrator is torn between his feelings of responsibility for Bartleby and his desire to be rid of the threat that Bartleby poses to the office and to his way of life on Wall Street. Ultimately, the story may be more about the narrator than Bartleby, not only because the narrator attempts to understand Bartleby's behavior, but also because of the rationales he provides for his interactions with and reactions to Bartleby. The narrator's detached attitude, towards life in general, and his compatriots in particular, seems to become increasingly compromised as the story goes on through his emotional and moral entanglement with Bartleby, culminating in the story's pivotal final line 'Ah Bartleby! Ah humanity!'[original research?]

Philosophical influences[edit]

Various philosophical influences can be found in 'Bartleby the Scrivener'. The story alludes to Jonathan Edwards's 'Inquiry into the Freedom of the Will'; and Jay Leyda, in his introduction to The Complete Stories of Herman Melville, comments on the similarities between Bartleby and The Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity by Joseph Priestley. Both Edwards and Priestley wrote about free will and determinism. Edwards states that free will requires the will to be isolated from the moment of decision. Bartleby's isolation from the world allows him to be completely free. He has the ability to do whatever he pleases. The reference to Priestley and Edwards in connection with determinism may suggest that Bartleby's exceptional exercise of his personal will, even though it leads to his death, spares him from an externally determined fate.[14]

'Bartleby' is also seen as an inquiry into ethics. Critic John Matteson sees the story (and other Melville works) as explorations of the changing meaning of 19th-century 'prudence'. The story's narrator 'struggles to decide whether his ethics will be governed by worldly prudence or Christian agape'.[15] He wants to be humane, as shown by his accommodations of the four staff and especially of Bartleby, but this conflicts with the newer, pragmatic and economically based notion of prudence supported by changing legal theory. The 1850 case Brown v. Kendall, three years before the story's publication, was important in establishing the 'reasonable man' standard in the United States, and emphasized the positive action required to avoid negligence. Bartleby's passivity has no place in a legal and economic system that increasingly sides with the 'reasonable' and economically active individual. His fate, an innocent decline into unemployment, prison and starvation, dramatizes the effect of the new prudence on the economically inactive members of society.

Themes[edit]

Bartleby the Scrivener explores the theme of isolation in American life and the workplace through actual physical and mental loneliness. Although all of the characters at the office are related by being co-workers, Bartleby is the only one whose name is known to us and seems serious, as the rest of characters have odd nicknames, such as 'Nippers' or 'Turkey', this excludes him from being normal in the workplace. Bartleby's former job was at the 'Dead Letter Office' that received mail with nowhere to go, representing the isolation of communication that Bartleby had at both places of work, being that he was given a separate work area for himself at the lawyer's office. Bartleby never leaves the office, but repeats what he does all day long, copying, staring, and repeating his famous words of 'I would prefer not to', leading readers to have another image of the repetition that leads to isolation on Wall Street and the American workplace.[16]

Rebellion and rejection are also expressed themes in this story. Bartleby refuses to conform to the normal ways of the people around him and instead, simply just doesn't complete his tasks requested by his boss. He does not make any request for changes in the workplace, but just continues to be passive to the work happening around him.[16] Just as public rejects changes from a normal routine, this rebellious style by Bartleby causes his co-workers to reject him as he is not behaving the same as the rest of the work place environment. The narrator tries multiple tactics to get Bartleby to conform to the standards of the workplace, and ultimately realizes that Bartleby's mental state is not that of normal society. Although the narrator sees Bartleby as a harmless person, the narrator refuses to engage in the same peculiar rhythm that Bartleby is stuck in.[17]

Publication history[edit]

The story was first published anonymously as 'Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall-Street' in two installments in Putnam's Monthly Magazine, in November and December 1853.[18] It was included in Melville's The Piazza Tales, published in by Dix & Edwards in the United States in May 1856 and in Britain in June.[19]

Reception[edit]

Though no great success at the time of publication, 'Bartleby the Scrivener' is now among the most noted of American short stories. It has been considered a precursor of absurdist literature, touching on several of Franz Kafka's themes in such works as 'A Hunger Artist' and The Trial. There is nothing to indicate that the Bohemian writer was at all acquainted with the work of Melville, who remained largely forgotten until some time after Kafka's death.

Albert Camus, in a personal letter to Liselotte Dieckmann published in The French Review in 1998, cites Melville as a key influence.[20]

Adaptations and references[edit]

Adaptations[edit]

- The story was adapted for the radio anthology series Favorite Story in 1948 under the name 'The Strange Mister Bartleby'. William Conrad plays the Narrator and Hans Conried plays Bartleby.

- BBC radio adaptation in 1953. Laurence Olivier plays the narrator, in this adaptation of Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street. Produced for the series of radio dramas 'TheatreRoyal', first broadcast by the BBC in 1953 and in the USA and was the only radio series in which Lord Olivier took a major role.

- The York Playhouse produced a one-act opera, Bartleby, composed by William Flanagan and James J. Hinton, Jr., on a libretto by Edward Albee, from January 1, 1961 to February 28, 1961.[21]

- The first filmed adaptation was by the Encyclopædia Britannica Educational Corporation in 1969; adapted, produced & directed by Larry Yust and starring James Westerfield, Patrick Campbell, and Barry Williams of The Brady Bunch fame in a small role.[22] The story has been adapted for film four other times: in 1972, starring Paul Scofield; in France, in 1976, by Maurice Ronet, starring Michel Lonsdale; in 1977, starring Nicholas Kepros, by Israel Horovitz and Michael B Styer for Maryland Center for Public Broadcasting, which was an entry in the 1978 Peabody Awards competition for television; and in 2001, as Bartleby, starring Crispin Glover.

- The story has been adapted and reinterpreted by Peter Straub in his 1997 story 'Mr. Clubb and Mr. Cuff'. It was also used as thematic inspiration for the Stephen King novel Bag of Bones.

- BBC Radio 4 adaptation dramatised by Martyn Wade, directed by Cherry Cookson and broadcast in 2004. Starring Adrian Scarborough as Bartleby, Ian Holm as the Lawyer, David Collings as Turkey, Jonathan Keeble as Nippers.[23]

- The story was adapted for the stage in March 2007 by Alexander Gelman and the Organic Theater Company of Chicago.

- In 2009, French author Daniel Pennac read the story on the stage of La Pépinière-Théâtre in Paris.[24]

- A novella by Katie Boyer entitled 'Bartleby The Scavenger' was published in the May/June 2014 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. While the setting is radically different, Boyer offers a Bartleby that is similar to Melville's in many ways.

- Bartleby, modern film adaptation: dir. Jonathan Parker, starring David Paymer and Crispin Glover, 2001.

- In 2018, Bartleby was retold by Matthew Mercier for the online literary magazine 'The Museum of Americana.' It retains the Wall Street setting, but updates the action, (or non-action, as it were) to the financial meltdown of 2008, and casts Bartleby as a stocks trader who 'prefers not to' participate in the sale of toxic, subprime mortgages. [25]

References to[edit]

Literature[edit]

- Bartleby: La formula della creazione (1993) of Giorgio Agamben and Bartleby, ou la formule by Gilles Deleuze are two important philosophical essays reconsidering many of Melville's ideas.

- In 2001, Spanish writer Enrique Vila-Matas wrote Bartleby & Co., a book which deals with 'the endemic disease of contemporary letters, the negative pulsion or attraction towards nothingness'.

- In her 2016 book My Private Property, Mary Ruefle's story 'Take Frank' features a high school boy assigned to read Melville's Bartleby. The boy unwittingly mimics Bartleby when he declares he would 'prefer not to'.

- In his 2017 book Everybody Lies: big data, new data, and what the Internet can tell us about who we really are, Seth Stephens-Davidowits mentions that one-third of horses bred to be racehorses never, in fact, race. They simply 'prefer not to,' the author explains, as he draws an allusion to Melville's story.

Film and television[edit]

- There is an angel named Bartleby in Kevin Smith's 1999 film, Dogma. He shares some resemblance to Melville's character.

- The 2006 movie Accepted features a character called Bartleby Gaines, played by Justin Long. The characters share similar traits and the movie uses some themes found in the work.

- In 2011, French director Jérémie Carboni made a documentary, Bartleby en coulisses, around Daniel Pennac's reading of Bartleby the Scrivener.[26]

- In 'Skorpio', the 6th episode of the first season of the television show Archer, Archer quotes Bartleby, and then makes reference to Melville being 'not an easy read'.

- In Chapter 12 of the novel Mostly Harmless by Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series, Arthur Dent decides to move to Bartledan, whose population does not need or want anything. Reading a novel of Bartledanian literature, he is bewildered to find that the protagonist of the novel unexpectedly dies of thirst just before the last chapter. Arthur is also bewildered by other actions of the Bartledans, but 'He preferred not to think about it'. (page 78). He notes that 'nobody in Bartledanian stories ever wanted anything'.

- In the Season 1 episode of Ozark entitled 'Kaleidoscope', Marty explains to his wife, Wendy, that when the potential for Del (the cartel) to ask Marty to work for him that he would respond as Bartelby would: 'I'll give him my best Bartelby impersonation, and I'll say, 'I prefer not to'.

- A story arc from sixth season of the American anime-style web series RWBY revolving around a species of monsters called 'The Apathy' is partially adapted from the story. A central, unseen character in the arc is named Bartleby as a nod to the title character.

Other[edit]

- The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek regularly quotes Bartleby's iconic line, usually in the context of the Occupy Wall Street movement.[27]

- The electronic text archive Bartleby.com is named after the character. The website's welcome statement describes its correlation with the short story, 'so, Bartleby.com—after the humble character of its namesake scrivener, or copyist—publishes the classics of literature, nonfiction, and reference free of charge'.[28]

- The British newspaper magazine The Economist maintains a column focused on the areas of work and management said to be 'in the spirit' of Bartleby, the Scrivener.

References[edit]

- ^Milder, Robert. (1988). 'Herman Melville.' Emory Elliott (General Editor), Columbia Literary History of the United States. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN0-231-05812-8, p. 439

- ^Bergmann, Johannes Dietrich (November 1975). ''Bartleby' and The Lawyer's Story'. American Literature. Durham, NC. 47 (3): 432–436. doi:10.2307/2925343. ISSN0002-9831. JSTOR2925343.

- ^Parker 2002: 150. (The opening sentence of the source is quoted there as well.)

- ^Knighton, Andrew (2007). 'The Bartleby Industry and Bartleby's Idleness'. ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance. 53: 191–192.

- ^Daniel A. Wells, 'Bartleby the Scrivener,' Poe, and the Duyckinck Circle'Archived March 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance, 21 (First Quarter 1975): 35–39.

- ^Christopher W. Sten, 'Bartleby, the Transcendentalist: Melville's Dead Letter to Emerson.' Modern Language Quarterly 35 (March 1974): 30–44.

- ^Leo Marx, 'Melville's Parable of the Walls'Sewanee Review 61 (1953): 602–627. Archived August 19, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^'Compassion: Toward Neighbors'. What We So Proudly Hail. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^Melville, Herman (1853). Bartleby the Scrivener.

- ^Schechter, Harold (2010). Killer Colt: Murder, Disgrace, and the Making of an American Legend. Random House. ISBN978-0-345-47681-4.

- ^Robert E. Abrams, 'Bartleby' and the Fragile Pageantry of the Ego', ELH, vol. 45, no. 3 (Autumn, 1978), pp. 488–500.

- ^ abMordecai Marcus, 'Melville's Bartleby As a Psychological Double', College English 23 (1962): 365–368. Archived January 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^'Pushing Paper – Lapham's Quarterly'. Laphamsquarterly.org. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^Allan Moore Emery, 'The alternatives of Melville's 'Bartleby', Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 31, no. 2 (September 1976), pp. 170–187.

- ^Matteson, John (2008). ''A New Race Has Sprung Up': Prudence, Social Consensus and the Law in 'Bartleby the Scrivener''. Leviathan. 10 (1): 25–49. doi:10.1111/j.1750-1849.2008.01259.x – via Project MUSE. (Subscription required (help)).Cite uses deprecated parameter

subscription=(help) - ^ ab'Barlteby the Scrivner: Theme Analysis Novelguide'. Novelguide. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^Walser, Hannah (2015). The Behaviorist Character: Action without Consciousness in Melville's 'Bartleby'. Department of English, Stanford University. pp. 312–332.

- ^Sealts (1987), 572.

- ^Sealts (1987), 497.

- ^Jones, James F. (March 1998). 'Camus on Kafka and Melville: an unpublished letter'. The French Review. 71 (4): 645–650. JSTOR398858.

- ^Stanley Hochman (ed.), 'Albee, Edward', in McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of World Drama: An International Reference Work in 5 Volumes, 2nd. ed., New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984, vol. 2, p. 42.

- ^'Britannica Classic: Herman Melville's Bartleby the Scrivener – Britannica Online Encyclopedia'. Britannica.com. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^'BBC Radio 4 Extra - Herman Melville - Bartleby the Scrivener'. BBC.

- ^'Le spectacle de Daniel Pennac au coeur d'un documentaire télévisuel vendredi soir – La Voix du Nord'. Lavoixdunord.fr. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^'The Museum of Americana'.

- ^'Le spectacle de Daniel Pennac au coeur d'un documentaire télévisuel vendredi soir – La Voix du Nord'. Lavoixdunord.fr. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^Big Think (August 28, 2012), Slavoj Žižek: Don't Act. Just Think., retrieved July 29, 2017

- ^'Welcome to Bartleby.com'. www.bartleby.com. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

Sources[edit]

- Parker, Hershel (2002). Herman Melville: A Biography. Volume 2, 1851-1891. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN0801868920

- Sealts, Merton M., Jr. (1987). 'Historical Note.' Herman Melville, The Piazza Tales and Other Prose Pieces 1839-1860. Edited by Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, and G. Thomas Tanselle. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library 1987. ISBN0-8101-0550-0

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Bartleby, the Scrivener at Project Gutenberg

- Bartleby, the Scrivener (Part I: Nov 1853) + (Part II: Dec 1853). Digital facsimile of first edition published in Putnam's Magazine. From the Making of America Archive.

- Bartelby, the Scrivener public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- The Strange Mister Bartleby Radio adaptation from the Internet Archive

Bartleby Student Success Unsubscribe Login

The Lawyer Quotes in Bartleby, the Scrivener

I am a man who, from his youth upwards, has been filled with a profound conviction that the easiest way of life is the best.

Unlock explanations and citation info for this and every other Bartleby, the Scrivener quote.

Plus so much more..

Get LitCharts A+ Already a LitCharts A+ member? Sign in!

Already a LitCharts A+ member? Sign in!Nothing so aggravates an earnest person as passive resistance. If the individual so resisted be of a not inhumane temper, and the resisting one perfectly harmless in his passivity; then, in the better moods of the former, he will endeavor charitably to construe to his imagination what proves impossible to be solved by his judgment.

To befriend Bartleby; to humor him in his strange willfulness, will cost me little or nothing, while I lay up in my soul what will eventually prove a sweet morsel for my conscience. But this mood was not invariable with me. The passiveness of Bartleby sometimes irritated me. I felt strangely goaded on to encounter him in new opposition… I might as well have essayed to strike fire with my knuckles against a bit of Windsor soap.

… Ah, happiness courts the light, so we deem the world is gay, but misery hides aloof, so we deem that misery there is none.

“At present, I would prefer not to be a little reasonable,” was his mildly cadaverous reply.

“…Good-bye, Bartleby, and fare you well.” But he answered not a word; like the last column of some ruined temple, he remained standing mute and solitary in the middle of the otherwise deserted room.

It was the circumstance of being alone in a solitary office, up stairs, of a building entirely unhallowed by humanizing domestic associations…which greatly helped to enhance the irritable desperation of the hapless Colt.

…charity often operates as a vastly wise and prudent principle—a great safeguard to its possessor. Men have committed murder for jealousy’s sake, and anger’s sake, and hatred’s sake, and selfishness’ sake, and spiritual pride’s sake; but no man that ever I heard of, ever committed a diabolical murder for sweet charity’s sake.

Yes, Bartleby, stay there behind your screen, thought I; I shall persecute you no more; you are harmless and noiseless as any of these old chairs… At last I see it, I feel it; I penetrate to the predestinated purpose of life… Others may have loftier parts to enact; but my mission in this world, Bartleby, is to furnish you with office-room for such period as you may see fit to remain.

…it often is, that the constant friction of illiberal minds wears out at last the best resolves of the more generous.

The yard was entirely quiet. It was not accessible to the common prisoners. The surrounding walls, of amazing thickness, kept off all sounds behind them. The Egyptian character of the masonry weighed upon me with its gloom. But a soft imprisoned turf grew underfoot. The heart of the eternal pyramids, it seemed, wherein, by some strange magic, through the lefts, grass-seed, dropped by birds, had sprung.

Dead letters! does it not sound like dead men? … Sometimes from out the folded paper the pale clerk takes a ring:—the finger it was meant for, perhaps, moulders in the grave; a bank note sent in swiftest charity:—he whom it would relieve, nor eats nor hungers any more; pardon for those who died despairing; hope for those who died unhoping; good tidings for those who died stifling by unrelieved calamities. On errands of life, these letters speed to death. Ah, Bartleby! Ah, humanity!